This is the story of the world’s first documented therapy dog. A cute little Yorkshire Terrier named Smoky, who charmed her way into the hearts of soldiers, sailors, airmen, doctors and nurses throughout the Pacific and the United States.

The tiny little dog’s travels are nothing short of extraordinary and her adventures from New Guinea, to Australia, to Biak Island, to the Philippines, Okinawa, and Korea and finally home to America made her a household name at the conclusion of World War II.

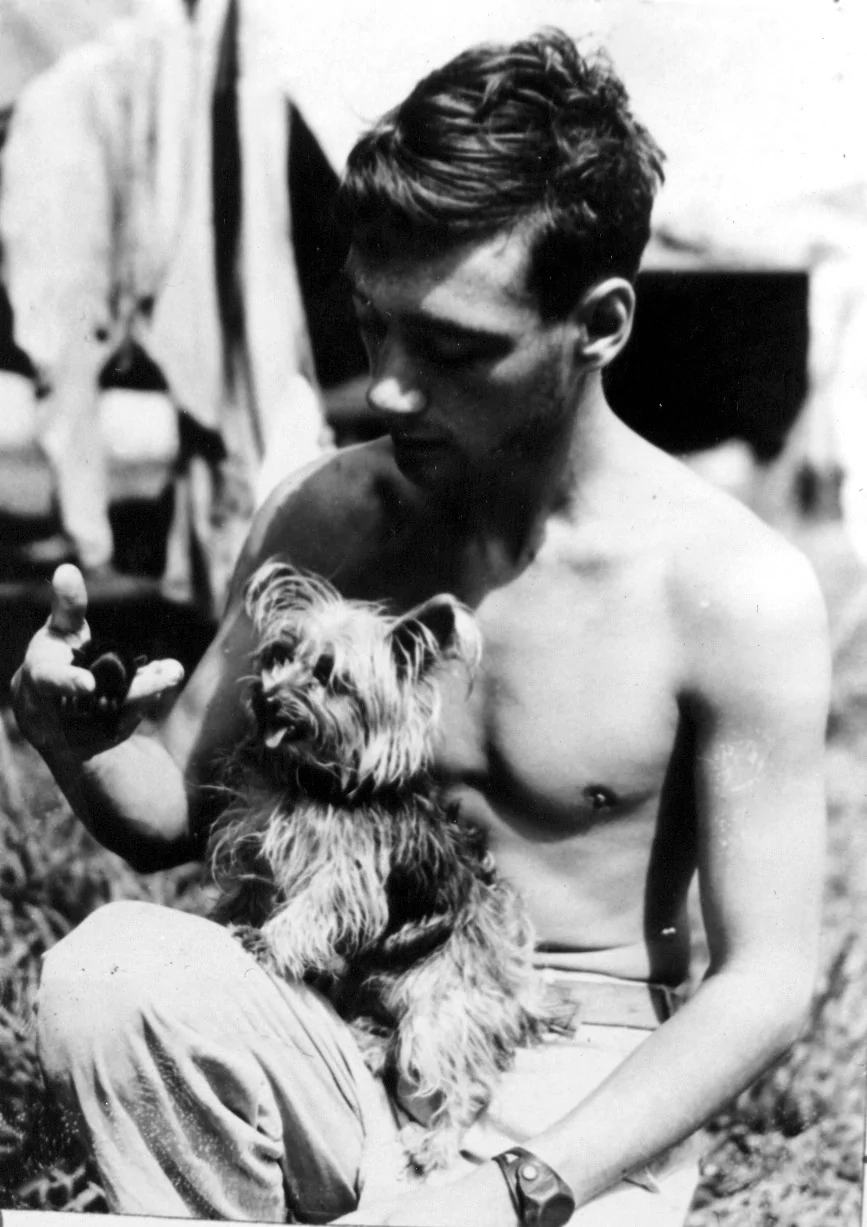

William ‘Bill’ Wynne trained with the US Army Air Force (USAAF) as an aerial photographer.

He was assigned to the aerial photography laboratory of the 5th USAAF, 26th Photographic Reconnaissance (Photo Recon) Squadron at Hollandia Airfield Complex, Nadzab, New Guinea.

In March 1944, Ed Downey who was Bill Wynne’s tentmate, was driving on a jungle road near the base when his Willys Jeep broke down. As he worked on the engine he heard a strange noise coming from somewhere in the surrounding jungle. He went to investigate the sound and soon found a little dog scratching in the dirt at the bottom of a foxhole.

Ed retrieved the little dog and brought her back to the base. Ed then gave the small dog to Airfield mechanic, Sergeant Dare. Soon after Bill visited Dare and saw the dog. Being a dog lover, he offered him two Australian pounds for the dog.

Dare wanted three pounds and as Bill mulled it over, he started wondering how he would care for a dog in a jungle environment, in the middle of a war. However, the next day Sergeant Dare went to the photo lab where Bill was working and offered to sell him the tiny dog to Bill for the original offer of two Australian pounds – the equivalent of $6.44 in US dollars at that time. This time Bill said yes, and decided to call her Smoky.

Taking care of a dog during wartime and in a jungle environment like New Guinea was challenging. After adopting Smoky, Bill faced the challenges of looking after her in the jungles of New Guinea – not the usual environment for a Yorkshire Terrier.

Bill gave Smoky daily baths in his helmet to keep her free of ticks and other insects. And with no dog food to feed her, he discovered Smoky liked bacon, ham, eggs, and bully beef.

Bill started teaching Smoky commands and tricks, which she learned quickly. So much so, Bill and Smoky began putting on shows for personnel at the base. Of course many at the base began to wonder where the dog came from, and how did she get there. Questions that would not be answered for some time.

In 1944, a contest was held to find “The Best Mascot of the Southwest Pacific Area.” Of course cute little Smoky won! Not long after, Bill woke up with a 105 degree fever and was taken to the US 233rd Field Hospital in Nadzab, where was diagnosed with dengue fever.

While in hospital some of Bill’s mates smuggled Smoky in and very soon, she won the nurses over. So much so, they asked to take her on rounds to “cheer up” the patients. While Bill was hospitalised, the nurses would pick up Smoky – who was allowed to sleep in Bill’s bed – every morning to go on rounds and would return her to Bill’s bed at the end of the day.

Following Bill’s discharge, his squadron doctor, Dr. Beryl D. Rosenburg, offered him some leave in Brisbane, Australia — with Smoky, of course. While in Brisbane, Bill was asked by Barbara Wood Smith, Assistant Field Director, with the American Red Cross to take Smoky to the US Navy 109th Fleet Hospital to visit the patients and cheer them up with a show.

Bill and Smoky performed in eight wards that day to the delight of all the patients and hospital staff. Barbara also asked if Bill and Smoky would visit the patients at the Brisbane US Army 42nd General Hospital. They performed in 12 wards there. The little dog brought smiles and joy to her audiences of injured, wounded, homesick, and war-weary troops.

Smoky brought so much joy to the troops, that in September 1944, Barbara Wood Smith wrote a thank you letter to Cpl. “Smoky” on official American Red Cross stationery. That letter read:

Dear Cpl. Smoky:

It has been several weeks now since you visited our hospital and I suspect that by now you and Bill are back at work. You should certainly feel a nice warm glow of satisfaction at all the pleasure you brought to the patients here at our hospital. They enjoyed your visit so much and are still talking about you. Some of them are boys who have lain in bed for months and have gotten very tired of looking at nothing but four walls and other sailors. We all know that laughter is something that helps people get better and you certainly administered enough of it here to improve the health of any number of our boys.

May we congratulate you for being that almost unheard of combination — a lady artiste without temperament! You entertained in eight wards that one afternoon and seemed just as full of energy and just as obliging at the end of your tour as at the beginning. The boys particularly liked your “dead dog” act and the way you jumped up and streaked after Bill when he gave you the word. We think that you’re a wonderful morale builder and we hope that you’ll have the opportunity to entertain a lot more boys later on, go back to Bill’s home in Cleveland and carry on the good work there.

There’s always a welcome for you here, where you and Bill will be pleasantly remembered.

Sincerely, and with thanks from all of us,

Barbara Wood Smith

Assistant Field Director

After two weeks in Australia, Bill returned to his squadron which had moved to Biak Island after its capture from the Japanese.

On September 16, 1944, Bill accepted an assignment with the 3rd Emergency Rescue Squadron looking for downed pilots. On his first mission he flew in a Stinson L-5 Sentinel. The aircraft sometimes flew 50 feet above the ground as they surveyed battle sites. They found a crash site, circled it three times and Bill took photos as proof of the crash and that there were no survivors.

When Bill returned from his first mission and the dangers of this type of flying were revealed to his mates, they asked Bill who would get Smoky if something were to happen to him.

On Bill’s second and future missions he (and Smoky) flew in a PBY Catalina. Bill and Smoky were crew additions and Bill explained to the crew that Smoky was a mascot and would bring them good luck. From then on, Smoky flew inside a canvas musette bag (a type of knapsack). When there was no combat/rescue action she sometimes ran around the plane.

The 26th Photo Recon next found a home in the Philippines. It was there that Bill said she went from being a pet companion to a bone fide war dog.

Communication lines needed to be run under a runway at Lingayen Gulf, Philippines. To complete the task with manpower, it would have taken around 70 men digging for approximately three days. It would have also shut down the airfield to Allied aircraft and with daily air attacks by the Japanese, the lives of many men could have been lost. Smoky, with a line attached to her collar, completed the job in about three minutes.

The 26th Photo Recon Squadron moved on from the Philippines to Okinawa and finally to Korea.

On November 1, 1945, the squadron received orders to return to the United States.

However, US Army regulations stated no animals will go back to the US on a War Department ship. Bill knew he couldn’t leave Smoky behind, so he devised a way to bring her aboard the ship in an oxygen carrying case.

Smoky made it on board. She never once barked, and the bag was not inspected. Bill found a top bunk in a corner – the bunks were stacked five high.

At the start of the voyage the ship encountered rough seas, and Bill was very seasick. He spent days sick in his bunk, so men from the 26th would sneak Smoky to the upper deck for “potty” breaks, forming a ring around her as they walked on the deck, to keep her hidden.

After managing to keep Smoky concealed, a US Navy officer looking for someone else discovered her. The officer asked if the dog was registered to be on the ship, to which Bill replied “no.” An hour later he was called to report to the ship’s office. He showed pictures of Smoky entertaining the sick and wounded, the letter from the Red Cross thanking Bill and Smoky for helping the morale of patients in the hospital and noted Smoky’s 1944 selection as ‘The Best Mascot of the Southwest Pacific Area.’ Bill was told he may have to pay a bond to bring the dog into the US which could be as much as $1,000 dollars. Bill agreed to the terms and he and the ship’s captain signed a document that cleared the ship of any responsibility for ‘one dog.’

With Smoky officially out of hiding, she and Bill put on shows for the men. Bill even noticed that the ship’s captain and the troop commander would sometimes watch the show from the bridge and had smiles on their faces.

On November 13 the USS William H. Gordon docked in Seattle.

After arriving in the US, Bill and Smoky’s story started to take on a life of its own. At one train stop on their way to Bill’s home in Ohio, a man with the USO noticed Bill carrying Smoky. After hearing their story someone called the Indianapolis Star. The newspaper ran a story which was picked up by a wire service.

Bill and Smoky finally arrived home in Cleveland, Ohio, on November 30, 1945.

A week after Bill arrived home the Cleveland Press asked to interview him. On December 7, 1945, the paper ran a front page story headlined, TINY DOG HOME FROM THE WAR. The New York Daily News, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun, and Herald America also published stories.

Smoky and Bill continued to entertain people after the war and performed at veterans’ hospitals, schools, orphanages, nursing homes, hospitals, and other organizations. They even became part of a children’s TV show in Cleveland, called Castles in the Air.

Bill eventually accepted a job with The Plain Dealer, a Cleveland newspaper, as a photographer. He would later become a photojournalist and was associated with the paper for 31 years. Bill received many awards for his work as a photojournalist and in 1973 was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

When Bill returned home from work on February 21, 1957, he found Smoky in her bed. She had died peacefully in her sleep. Bill admitted he was inconsolable. His wife Margie suggested they bury the little dog near ‘Our Tree.’ – a tree that a young Bill and Margie had carved their initials into, years before. The next day, with their children, Bill and Margie found the tree, and with Smoky’s body in a shoebox they buried her.

Josephine Robertson, a writer at The Plain Dealer, wrote an obituary for Smoky and told her wartime story. A local Cleveland woman, Grace Guderian Heidenreich, read the obituary and telephoned Bill and Margie. Grace was a US Army nurse in New Guinea in early 1944. Her fiancé at the time and later her husband, had bought a Yorkshire Terrier for her from a veterinarian in Brisbane. The dog was a Christmas holiday gift, so Grace named her ‘Christmas.’ (Christmas was one of the words that got Smoky excited and turning in circles.)

Following Grace’s attendance at a Bob Hope USO show in New Guinea, little ‘Christmas’ disappeared. She had photos of the dog to show Bill. As the stories merged, Bill concluded that his little dog, found in a foxhole, was indeed one in the same. How many Yorkshire Terriers in WWII were lost in the jungles of New Guinea during World War II?

In 2003 Bill was informed that a monument to honour Smoky would be placed near the beech tree in the Rocky River Reservation Metropolitan Park in Cleveland, where Smoky was buried in 1947.

Bill searched for Smoky’s grave for hours before finally finding the then fallen beech tree – with its initials – which led to finding the grave. Smoky’s remains were placed in a WWII .30 calibre ammunition case. The monument marks Smoky’s grave and was unveiled on Veterans Day, November 11, 2005.

On April 19, 2021, Bill Wynne passed away at the age of 99.

Purple Cross awarded by the RSPCA.

animals in Australia.